|

Print

Version

URBAN LAND, HOUSING, AND TRANSPORTATION: THE

GLOBAL CHALLENGE

Sir Peter

Hall

We’re just passing one

of the great milestones in human history – but hardly anyone is

noticing. It isn’t anything outwardly dramatic, like a revolution or a

war. But it is fundamental, in the sense that the Industrial Revolution

in Britain was fundamental. Future historians, doubtless, will call it

the Urban Revolution. For the first time in

history, a majority of the world's six billion people are living in

cities. Between 2000 and 2025, on the best estimates we have from the

United Nations, the world's urban population will double, to reach five

billion; city-dwellers will rise from 47 percent to over 61 percent of

the world's population.

But that’s not all.

Most of this explosive growth will

occur in the cities of the developing world. There will be a doubling of

the urban population, in the coming quarter century, in Latin America

and the Caribbean, in Asia and in Africa together – above all in

Asia and Africa. Even by 2015, the UN predict that there will be 358 "million

cities", with one million or more people; no less than 153 will be in

Asia. And there will be 27 "mega-cities", with ten million or more

– 18

of them in Asia. It is here, in the exploding cities of some of the

poorest countries of the world, that the central challenge lies.

A huge challenge, to be

sure – but also a huge range of opportunities: opportunities for greater

freedom, greater freedom above all for development, as people leave

behind their traditional bondage to the land and the total dominance of

the daily struggle for food. Urbanization is a fundamental form of

liberation of the human spirit: in the famous German quotation from the

Middle Ages, Stadtluft macht Frei: the city air makes you free.

It does more than that: just because it frees up human creativity, the

city is the place where the great advances occur – artistic,

intellectual, technological and also organizational. You need

urbanization if you’re going to get development. Urban growth is

potentially a great thing.

Table 1 World Urban

Population, 1980-2000-2020

But only potentially.

Urbanization is a basic precondition for development. But it doesn’t of

itself guarantee development. There’s good urban growth and there’s bad

urban growth. Managing urban growth so that it contributes positively

to economic advance, reconciling it with ecologically sustainable forms

of development and reducing social exclusion, represents the key

challenge for urban planners and urban managers in this new century.

The Fundamental Challenge

The major challenge,

for those of us who care about cities, comes from the burgeoning

cities of the developing world, where there is a paradox: people are

still flooding into these cities, too many children are being born in

those cities based on the hope for a better life; but too often they are

being cheated. For urban growth has brought a sharp rise in urban

poverty: according to UNFPA estimates, over one in four

of the people in the cities of the developing world

lives below official poverty lines, and that proportion rises to more

than one in three in the Middle East and North Africa and to more than

two in four in sub-Saharan Africa. And a large proportion of the

poorest are women.

In these cities, the

quality of the environment is not improving; in far too many cases, it

is deteriorating. The problem is daunting. Many of these cities are

already bigger than their equivalents in the developed world, and are

projected to become yet larger. Most have only recently started on

their development process. And, with some conspicuous exceptions, they

lack the governmental structures and the administrative traditions to

tackle the resulting problems. Let’s be fair: they have achieved a

great deal against overwhelming odds; and some have emerged as models

for the rest of the world. But they are too few, and their example is

not spreading fast enough.

Three Kinds of City: Three Kinds of Problems

However, and this is the first important point I want to make, the term “developing city”, like the term “developing country”,

is no longer very meaningful. In fact, I want to argue that it’s

fundamentally confusing. The World Commission on 21st-Century

Urbanism, which presented its report Urban Future 21 to a major

conference in Berlin in the year 2000 (Hall and Pfeiffer 2000), argued

that we can most usefully divide cities worldwide into three major

categories, and that so-called “developing cities” in fact fall into two

different categories. Even this is crude and simplistic, but it makes

the point.

The first category the Commission called the City

Coping with Informal Hypergrowth. It is represented by many

cities in sub-Saharan Africa and in the Indian subcontinent, by the

Moslem Middle East, and by some of the poorer cities of Latin America

and the Caribbean. It is characterized by rapid population growth, both

through migration and natural increase; an economy heavily dependent on

the informal sector; very extensive

poverty, with widespread informal housing areas; basic problems of the

environment and of public health; and difficult issues of governance.

The second type the Commission called

the City Coping with Dynamic Growth. It is the characteristic city

of the middle-income rapidly-developing world, represented by much of

East Asia (including China), some of South Asia, much of Latin America

and the Caribbean, and the Middle East. Here, population growth is

falling, and some of these cities face the prospect of an aging

population. Economic growth continues rapidly, but with new challenges

from other countries. Prosperity brings environmental problems.

The

City Coping with Informal Hypergrowth

In this first kind of city,

the key problem is that the urban economy can’t keep pace with the

growth of the people. There are high birth rates – a product of sexual

ignorance, superstition and above all poorly-educated, often illiterate

women. This, plus continued migration from the countryside, produces a

huge surplus of unskilled labor. Many of the migrants have been pushed

off the land rather than positively pulled into the cities, by famine or

civil war or insurrection: too often, they are virtually starving. They

go into the only work they can find, in the informal economy: casual

work and petty trading. This leaves them in dire poverty – especially

the women and above all the female-headed households, which typically

form more than 30 percent of the poor population.

The problem is that in

these cities the formal or modern sector is too often struggling to

survive, and too often giving up the battle. This is particularly true

of indigenous enterprises. They can’t compete, for multiple reasons:

under-education, poor infrastructure, lack of credit, and failure to

access global markets. So you find cities that – apart from global

enterprises like hotel chains or fast food outlets – lack a formal

economic base, cities in which the great majority of people live in

informal slums, often in very bad conditions, and eke out an existence

in the informal economy. They have little work and they live at the

margins of existence, in places that lack the basics for a civilized

life. They have little concern for the environment, because they can’t

afford to do anything except struggle for survival: if keeping warm

means cutting down the remaining trees for firewood, they’ll do it; if

keeping alive means drinking polluted water, they’ll do that. And they

find it hard to connect with worthwhile jobs, even if they had the skills,

because they can’t physically reach them: lacking either a bicycle or a

bus fare, they have nothing but their own two feet.

If you visit such cities, your first

reaction may well be despair. But there is actually a solution to

this huge raft of problems, though it may sound paradoxical.

First, it is to get the birth rate down, which means basic

education, above all education for the girls. Our report argues that

there’s a tremendous role for information technology here, if we can get

low-cost machines that don’t need to depend on erratic

electricity service. In fact technology has taken a huge leap even in the five

years since we were working on our report, through the development of

battery-powered mobile phones that can hook up directly to the

Internet. And this is just the beginning.

Then, the key is

progressively to formalize the informal economy. Cities can do this in

various ways: strengthening relationships to the mainstream economy,

both for inputs and outputs – for instance, by providing

microcredit, building materials, food and water, and more

effective transportation to help people gain access to a wider range of jobs.

They can achieve this best through communal self-help neighborhood

projects, backed up by informal tax levies to pay for materials, which can

help overcome bottlenecks in basic infrastructure. Microcredit,

providing tiny loans so people can start their own businesses, will play

a particularly crucial role.

The

City Coping with Dynamic Growth

Here there’s good news: the trend is for population growth to

fall sharply, because of urbanization, as people see that the costs of

education and rearing children rise while the economic value of children

goes down. (These are two sides of the same coin: crudely, the value of

uneducated young people tends to decline, so it simply takes much longer

and costs more to get them to the point where they become effective

earners). And this has further impacts: there is a big rise

in the number of working-age people relative to the young and the old,

who have to be looked after. In the jargon, the dependency ratio falls

to a minimum.

So that’s the good news,

and it isn’t the end. In these cities, the great passage from the

informal to the formal economy is already well under way. Many of them

are very attractive to inward investment, because they offer a

well-educated and well-trained labor force at lower wages than in

developed cities, and besides, economic growth is generating big domestic

markets for consumer durables like cars and refrigerators and personal

computers. China is the outstanding case here, following on a hugely

bigger scale the example earlier set by “tiger economies” like

Singapore, Hong Kong or South Korea. But there’s a sting in the tale

there: this foreign direct investment can always be diverted to even

lower-cost countries and cities, as some Latin American cities are now

unfortunately discovering. The key is to keep trading up into more

sophisticated levels of production, especially advanced services, as

both Singapore and Hong Kong have done during their four decades of

sustained growth, and as leading Chinese cities like Shanghai are now

doing.

The main result of all this

is that cities in this group all find themselves in a state of quite

extraordinary dynamism but also of rapid transition. It often seems as

if they’re going through every stage of economic development at once.

Or rather, different sections of their population are going through

different stages. Side by side, in the downtown business districts you

can see gleaming new high-rise office towers full of global corporations

that provide advanced business services; along the arterial expressways,

sleek suburban factories that are pouring out consumer goods as well as

forests of new apartment towers; and, in between, wretched informal slum

settlements where the people struggle to make a basic living by

performing odd jobs or selling trinkets. These cities often look as if

they’re simultaneously first world cities and third world cities.

One result is that they are

highly polarized. Many of them, though not all, display

extraordinary contrasts in wealth and poverty. Cities in South

Africa and Brazil, two of the most unequal countries on earth, display

this pattern to an extreme degree – but it’s now observable in China and Poland. A

significant sign is to see heavily gated, even armed luxury apartment

blocks or country-club type developments, next to wretched shacks or

worn-out slum apartments. All too often, in many though not all of

these cities, there are reports of escalating crime and violence. The

poor, some of them, may find solace in drink or drugs, compounding the

problem. Because the poor have to find somewhere to live, they often

contribute to environmental disasters by building their homes on

unstable hillsides or on floodplains, with results that are sometimes

tragic. Even when they and their homes survive, they are often located

far from job opportunities, with poor or non-existent bus services,

compounded by traffic congestion.

The answer to these

problems is to continue to push the economy in the direction first of

advanced manufacturing and then of advanced services, always keeping one

step ahead of the global competition. (Again, Eastern Asian cities

provide the classic model). Of course, cities cannot provide all the

necessary policies on their own: nation-states have to provide the right

framework of macroeconomic policies. But cities can do a lot,

especially if they are given the right degree of administrative and

fiscal autonomy – which many of them have been getting, already, during

the last two decades. Above all, they must and they can help their

poorest citizens to join the mainstream economy and the mainstream

society.

Then

and Now…

It’s helpful at this

point, I think, to turn from a geographical kind of comparison to an

historical-geographical comparison. In some important ways, not least

income levels, cities in this group compare with cities in the mature

developed world about a hundred years ago. London, Paris, Berlin, New

York in 1907 can be compared with São Paulo, Mexico City, Caracas and

Bogotá today. Both groups of cities were, or are, growing explosively

both in population and wealth. Both displayed, or display, extreme

divisions of wealth. Both contained, or contain, huge high-income

areas of great affluence and also huge slum areas of great

wretchedness. But there are, I would argue, two key differences.

The first is in housing.

Then, the slums had a formal characteristic: they were of permanent

construction, generally large houses built for wealthy people (as in

London), sometimes apartment blocks (as in Paris or New York),

subdivided and sometimes again subdivided, and therefore chronically

overcrowded. Now the corresponding slums are informal: self-built and

unserviced. In fact, they correspond very precisely to the slums of the

first category of cities, which shows us that this second category is

really an amalgam of the first type and the fully-developed mature city.

The second key difference

was, or is, in transportation. The basic reason for the slums of 1905 was

that the poor, who depended on informal employment, had to crowd ever

more closely into housing near their work – that is, in or near the city

center. In London at that very time, the great social reformer Charles

Booth wrote a paper entitled

Improved Means of

Locomotion as a first Step towards the Cure of the Housing Difficulties

of London

(Booth 1901).

And in fact, just that was happening. Already, London had

the world’s first underground railway; in 1900, it was already nearly 40 years old. And, aided by American capital, the

tunneling teams were burrowing under London’s streets. Most of the

tube network, on which you travel if you visit London today, was built

by the year 1907. And simultaneously, the municipal authority for

London, the London County Council, was electrifying and extending the

tramcar system to serve new public housing estates, offering very low

worker’s fares so that poor people could afford to live in good housing

on the edge of the city while getting to their jobs in the center.

Many developing cities today, in contrast, are in some cases very much

larger – the São Paulo metropolitan area is three times the size of

London a century ago – yet have much less well-developed public

transportation systems. The paradoxical, even perverse, result is that

relatively speaking, the poor in these cities have much greater problems

in getting to work than their counterparts in London or New York in

1907.

Housing in the Developing World

How adequate is housing

in the developing world? UN-Habitat figures show a mixed picture. Very

evident is the fact that two areas – Latin America and the Caribbean,

and Asia – show far better standards than Sub-Saharan Africa, or North

Africa and the Middle East. The same is evident for provision of basic

infrastructure like water, sewerage, electricity or telephone service.

To a remarkable degree, throughout the developing world, most housing is

well-serviced. But for informal housing, this position varies

considerably. Generally, however, provision in Sub-Saharan Africa falls well

behind that in the rest of the developing world.

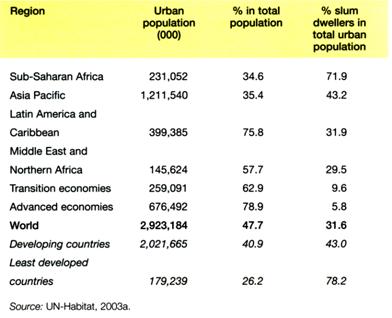

That raises the basic

question; what is sub-standard housing? How do we define a slum? UN-Habitat has sought to produce a rigorous, generally-applicable

definition. They use five key elements: access to water, access to

sanitation, structural quality of housing, overcrowding, and security of

tenure. Using that as the basis, Table 2 from UN-Habitat shows the

relative proportion of slum housing by region, worldwide, in 2001.

Overall, slum dwellers constitute 32 percent of the world’s urban

population. For developing countries, the figure is 43 percent; for the least

developed countries, 78 percent. This represents a huge differential

between Sub-Saharan Africa and the rest of the developing world.

Table 2 Distribution

of the World’s Urban Slum Dwellers, 2001

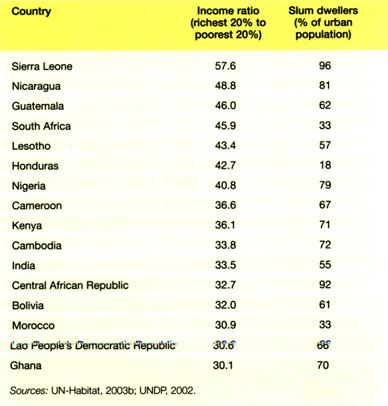

Slum development is

systematically associated statistically with GDP per capita and with the

UNDP’s Human Development Index. But there is a striking systematic

relationship between the prevalence of slum housing and inequality of

income (rather than absolute income), as Table 3 shows. The UN-Habitat

analysis suggests that generally throughout the developing world,

despite rising per capita income levels, housing is becoming less rather

than more affordable, both for owners and renters. But there are major

differences between the least and the most developed regions: Latin

America appears quite highly developed in terms of housing

affordability, suggesting that the process of formalizing informal

settlements has been successful overall. Rather remarkably, most

inhabitants of informal housing do not squat rent-free, but pay rent to

a landlord. This suggests the degree to which there is an incentive to

own.

Table 3 Slums and

Income Inequality

Housing and Transportation: The Pacific Asian and Latin American Ways

One important key for the

people in such areas is to help them formalize their housing: to use

communal self-help to provide the necessary infrastructure, so that they

begin to turn their informally-built areas into middle-class

neighborhoods. In countless Latin American cities, it has been

happening and is still happening. In many eastern Asian cities, the

approach has been different: the city itself has intervened to tear down

informal neighborhoods and provide high-quality housing, first for

rent, later for sale, either through public provision or, increasingly,

by policies that foster the growth of owner-occupation, as in

Singapore. There is no one right way here; there are different paths

towards the same goal.

The UN-Habitat 2003

report contains a number of urban case studies, several located in

Latin America. Bogotá demonstrates forty years

of “informal” growth – here, mainly not due to squatting, but to illegal

subdivision. Vast settlements such as Ciudad Bolivar, Bosa, and Usme at

first lacked water, drainage, sewerage, power, education, and health

care. But they saw consistent improvement, in which the city

authorities worked collaboratively with local inhabitants (UN-Habitat

2004, 88).

In Bogotá, which is characterized by a

special form of low-income neighborhood called the barrio pirata

("pirate" neighborhood), formed not through land invasions but through an

informal process of land subdivision and granting of title, there has

recently been a huge “de-marginalization mega-project”, which between

1998 and 2000 used a budget of US$800 million to construct 110

kilometers of local roads, 2300 kilometers of drainage, six hospitals,

51 schools, 50 parks, four major public libraries and legalizing 450

settlements. It did not fully achieve these targets, falling

significantly short on surfacing and lighting of roads, partly because

it depended on the sale of a telephone company that failed to go through

– but it is nevertheless impressive. The problem, as in so many other

Latin American cities, is that though the city achieved measurable and

significant improvements on key measures,

none the less poverty rose sharply (from 35 percent below the official poverty

line in 1997, to 49.6 percent in 2000) and income inequalities grew as more and

more internal refugees flood into the city escaping political violence

outside, causing new household formation to surge ahead of housing

provision (Skinner 2004, 80-1).

São Paulo demonstrates that there are two distinct

kinds of slum: corticos (rented rooms in subdivided inner-city

tenements), of very poor quality but close to jobs and urban services,

and favelas, found everywhere, but for the fact that in the city

itself, private owners tended to regain possession of squatted areas –

two only survive here, both very large (Heliópolis

and Paraisópolis) but the great majority are now found in the poorest, peripheral, environmentally-fragile

areas (UN-Habitat 2004, 89).

Mexico City produces two

case studies in the UN-Habitat 2003 report. The first, Nezahualcóyotl,

concerns a huge irregular settlement that

developed from the 1950s on a drained lake bed outside the Federal

District. Here, legal title was ambiguously legal: speculators “sold”

plots and the state government subsequently regularized title. But the

resultant developments lacked basic services such as paved roads,

lighting, water, and main sewerage. From the end of the 1960s a

citizens’ movement, Movimiento Restuarador de Colonos,

successfully campaigned to secure progressive legalization of titles and

basic servicing, even extending, at the Millennium, to extension of the

Metro transit system outside the Federal District. As a result, by the end of the

1990s, only 12 percent of the area was still held in irregular title. But the

quality of basic services varies greatly: 63 percent of households have inside

water supply, but 15 percent still have poor roofing (UN-Habitat 2004, 94).

The second Mexico City

case study concerns the Valle de Chalco Solidaridad, a vast

informal settlement southeast of the Federal District. This was an

agricultural area, where in the early 20th Century, after the Mexican

revolution, the land was expropriated and given to the peasants. But

after 1950 the plots became uneconomic to farm at just the time when,

resulting from urban sprawl, the land became attractive to speculators.

The land was subdivided and sold on credit, and between 1970 and 2000

the population rose from 44,000 to 323,000. Here too, by 1998, 90

percent of

the plots had regularized title, and major infrastructure had taken

place. Even so, at that date basic housing conditions remained very

bad: 78 percent of households had no inside water, 40 percent still had cardboard

roofing, and 20 percent of households lived in one room (UN-Habitat 2004, 91).

The conclusions from

these UN-Habitat case studies are very clear, and they give mixed

signals. Informal settlements tend quite rapidly to become regularized,

and their inhabitants to receive legal title, while services are

progressively provided: first basic ones like piped water, sewers, paved

streets, and street lighting, then more advanced services like schools,

libraries, and even public transportation service. But the resultant provision is still

incomplete, with different standards. Meanwhile, the entire

invasion/improvement process ripples ever farther out from the urban

core, bringing a problem of access to jobs, with long commuting

distances and even longer times. As a result, the quality of transportation

service becomes crucial.

Here, too, there is a basic

difference in approach. Some Eastern Asian cities have deliberately

encouraged high-density development which support top-quality

rail transportation systems – and some, like Hong Kong and Singapore, had no choice

because they had so little land. China seems to be going the same way,

as can be seen in Shanghai. Some Latin American cities, in contrast,

have made extraordinary innovations in operating bus systems to serve

their more far-flung residential neighborhoods – and one of the most

extraordinary of all, Curitiba in Brazil, has created a bus system that

works like a metro railway service, with local buses that feed into an express system

traveling on its own tracks; Bogotá in Colombia has developed a very

similar system.

Latin American cities,

above all Brazilian cities, have taken a world lead over the past three

decades in developing highly innovative urban bus-based transit systems.

For this there have been very good reasons. As we have seen, rail-based

metro systems have been far less developed, especially 30 years ago;

Brazilian cities simply lacked the resources for expensive tunneled

rail systems, and made a virtue out of necessity. Curitiba’s “Bus

Metro” system was the great pioneer, widely hailed and now widely

imitated in cities as diverse as Bogotá, São Paulo, and many

others. Brazilian engineers took the lead in developing these

solutions. But at their best they involved not just engineering but

also planning approaches, since they integrated bus service and land-use

planning.

The central feature of

the Curitiba system is a variety of services – express buses running

along special bus corridors, orbital services, and local services, all

integrated through high-speed transfer stations at a variety of points

all over the city, and used as the basis of a land-use policy that

encourages high-density development and redevelopment along the express

corridors. The buses on the express corridors are very high-capacity

bi-articulated vehicles with a total capacity of 270, more akin to a

light rail train than an ordinary bus. Painted red, they interchange at

the transfer stations with buses running on orbital routes from suburb

to suburb, painted green, and with local feeder or “conventional” buses

painted yellow. The comparative capacities of the buses on the

different systems vary greatly. All are operated privately on a

franchised system. The express corridors have been deliberately

developed through planning and zoning controls for very high-density,

high-rise mixed development – as is very evident from the tourist’s view

from the top of the city’s television tower.

Thus Curitiba’s success

became a Brazilian success. Brazilians make over 60 million bus trips a

day; Americans, living in a country with twice the urban population,

make only one third as many. Brazilian cities demonstrate some of the

highest rates of bus ridership in the world: São Paulo and Rio between

them have about as many daily bus journeys as the entire United States,

which has ten times their combined population. All the major Brazilian

cities have made major innovations in bus operation: in the 1970s, São

Paulo and Porto Alegre pioneered the idea of running buses in convoys

along a dedicated lane, and Porto Alegre developed an integrated

paratransit system. These innovations were driven by necessity:

bus-based transit systems average $5 million per mile ($3 million per

kilometer) against $20-$100 per mile ($12-62 per kilometer) for light

rail or metro subway systems. The success of these bus-based solutions – urban

bus operations in Brazil yield positive net revenues of over $3 billion

per year – have created a flourishing export industry, with worldwide

consulting operations; the engineer Pedro Szasz, who developed the bus

convoy systems in São Paulo and Porto Alegre, engineered the combination

of local, skip-stop, and express services that constitute the

Transmilenio Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system in Bogotá (Golub 2004, 4-5;

Skinner 2004, 78).

But there’s an odd point:

if you visit Singapore and Curitiba, the two cities look very alike,

because both have integrated their land-use and transportation policies,

encouraging high-density and high-rise development along their main

transportation corridors. Again, there’s more than one way towards the

same goal, but in the end the outcomes may be very similar.

It’s no accident, perhaps,

that Curitiba and Singapore are now two of the richest cities in this

group; in effect both have made the transition into the developed world,

and both are technologically and organizationally among the world’s most

advanced cities. These cities are leading their countries in

technological and organizational innovation, showing the way for other

cities either to imitate them or to go in a different, equally

innovative, direction. That is the path of rapid development.

There are some important

conclusions, therefore, regarding transportation. Latin American cities

demonstrate that bus-based cities do work: they can deliver good

service, with high passenger volumes, at remarkably low cost. But there

is a basic question. Can they do so everywhere, especially to the

urban periphery? If they fail to do this, is the urban transportation

problem in the largest cities destined to become steadily worse? I want

to argue that it will not, because of the emergence of a new urban

phenomenon: the Mega-City Region.

A New

Urban Phenomenon: The Mega-City Region

Another key difference

between the great cities of a century ago, and now, is this new

phenomenon: the Global Mega-City Region (MCR). This is a pattern of extremely

long-distance deconcentration stretching up to 150 kilometers from the

center, with local concentrations of employment surrounded by

overlapping commuter fields, and served mainly by the private car. The

Pearl and Yangtze River Deltas in China and South East England, around

London, are two of the world’s leading examples of this phenomenon. In

Pacific Asia, it has recently been predicted that by 2020, two-thirds of

the population of the ASEAN group of countries will be found in only

five MCRs: Bangkok (30 million), Kuala Lumpur-Klang (6 million), the

so-called Singapore Triangle (10 million), Java (100 million) and Manila

(30 million). In adjacent Eastern Asia, these agglomerations are even

bigger: Japan’s so-called Tokaido corridor

(Tokyo-Nagoya-Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe) is predicted as having a total

population of 60 million, China’s Pearl River Delta (Hong

Kong-Shenzhen-Guangzhou) 120 million, and the Yangtze River Delta

(Shanghai-Suzhou-Hangzhou-Nanjing) 83 million (McGee 1995, Wo-Lap 2002,

quoted in UN-Habitat 2004, 63).

The precise spatial details vary from

country to country according to culture and planning regime, and for

this reason population figures and predictions should be treated with

caution, but the pattern is emerging very clearly and very rapidly

around some of the largest cities in this second category: it is quite evident around São Paulo, and has recently been

analyzed in some

detail by Adrián G. Aguilar and Peter M. Ward for Mexico City (Aguilar

and Ward 2003).

Latin America is highly

urbanized. In 2000, in Latin America and the Caribbean, 75.4

percent of the

total population, 400 million, were urban; 31.6 percent of the total

population and 41.8 percent of the urban population lived in cities of more than

one million, while 15.1 percent of the total population and 31.5 percent of the urban population

lived in metropolitan areas with 5 million and more people. And these included some

of the biggest urban agglomerations in the world: Mexico City, with 18.1

million, 2nd largest in the world; São Paulo, with 17.9 million, 3rd; Buenos Aires, with 12

million, 11th; and Rio de Janeiro, with 7.4 million, 15th. Also in this

list were Bogotá (6.8 million) and Santiago (5.5 million) (UN-Habitat

2004, 64).

However, it is extremely

important that the term “city”, in this sense, is not the administrative

entity but a much larger metropolitan area. In the largest cases, such

as Mexico City and São Paulo, it is in fact an equivalent of the Asian

Mega-City Region. These Mega-City Regions develop through a complex

process of simultaneous decentralization at a regional scale, and

recentralization at a more local scale: a process that Dutch planners in

the 1960s called “concentrated deconcentration”. Thus they are

increasingly polycentric. In recent decades, it has been observed that

central city growth has slowed while peripheral growth has speeded up.

As the UN-Habitat 2004/5 report notes, “…significant shifts from

city-centered to regional forms of urbanization are currently taking

place” (UN-Habitat 2004, 65): multi-nodal, urbanized regional systems are

developing, in which new sub-centers are independent in terms of their

social and economic patterns, but are functionally linked to the big

city, a process that in a recent European study we have termed

functional polycentricity (Hall and Pain 2004). In the Mexico City

metropolitan region, more than half the population lives outside the central

Distrito Federal, which is generally regarded as the city. In São

Paulo, the city contains 10 million people, just half that found in the

wide metropolitan area (19.8 million). In Buenos Aires, out of a total

metropolitan population of 12 million, only 3.5m live in the Capital

Federal (UN-Habitat 2004, 65-66).

Failure to appreciate or

understand this process has led to some quite serious errors. In the

1970s, urban analysts incorrectly predicted further explosive growth of

metropolitan areas: Mexico City for instance was predicted in UN publications

as growing by the year 2000 to 30 million. In fact, almost as these

predictions were being made, growth tapered sharply and stopped at the

20 million point. There were two reasons for this, neither having

much to do with planning. First, because of obvious

emerging negative externalities in the Mexico City metropolitan region,

migrants from rural areas diverted to second-order cities such as

Guadalajara and Monterey. Secondly and even more significantly,

within the general area of Mexico City, population growth diverted to “secondary cities” at increasing

distances, many informal settlements of vast size such as Nezahualcóyotl

and Ecatapec, located in the adjacent State of Mexico (UN-Habitat 2004,

50, 65).

Aguilar and Ward show that

Mexico City’s Federal District is now merely the core of a huge and

polycentric Mega-City Region stretching up to 100 kilometers and more

from the Zócalo. In fact more than half the population of the region is

now found outside the Federal District. Over the last 35 years, population

growth has rippled out in concentric circles at steadily increasing

distances from the city center, and the most rapid growth is now in the

peripheral areas. This outer zone is characterized by huge informal

settlements like Ecatapec and Nezahualcoyotl, with up to one or two

million people apiece. Very significantly, these settlements suffered

from serious deficiencies in basic infrastructure three decades ago, but

had largely caught up by the 1990s (Aguilar and Ward 2003, passim). I

will return to that point a little later.

Equally important however

is another point: these outer areas are not just vast residential

zones. They now contain economic sub-centers that are increasingly

important in their own right. And in this process, which could be

called the increasing "polycentralization" of the metropolitan region, there is an

increasing specialization of function: the more advanced or formal parts

of the economy remain within the Federal District, even in its core,

while the outer centers attract manufacturing and retail functions.

To the north these are dominated by heavy, large-scale and

high-technology enterprises such as metal and chemical industries; to the east, they

are dominated by small-scale informal activities; in some parts of this

zone, significantly, there was a decline in employment in traditional

craft industrial employment. But there was also a notable growth of

services and trade activity in this zone along major transportation corridors (Alguilar

and Ward 2003, 15-16).

This process has distinct

advantages. As jobs develop in the outer rings of these metropolitan

areas, the burden of commuting can lessen. In Bogotá, though population

grew by 40 percent, travel distances have stayed the same (UN-Habitat

2004, 52).

The

Basic Emerging Problem: Governance in the Mega-City Region

There is currently a

basic problem with all these Mega-City Regions: they suffer from

fragmented governance. The Mexico City metropolis has 28

municipalities, and more than half the population lives outside the

Distrito Federal. The São Paulo metropolitan region is similarly divided

among 39 districts and municipalities; Rio de Janeiro among 13

municipalities, and Buenos Aires among 20 municipalities that enjoy

varying degrees of autonomy; the Curitiba metropolitan area is governed

by no less than 25 municipalities (UN-Habitat 2004, 58, 66). This last

case is particularly significant: within the Curitiba metropolitan area

the population of the city accounts for only 61 percent of

the population – and is falling. And, despite the legendary worldwide

reputation of the city for delivery of highly innovative services, the

evidence from the wider region is far less encouraging: 500,000 live

below the Brazilian official poverty line, there are 89,000 substandard

dwelling units in 903 problem housing areas, only 58 percent of the area is sewered and

only 35 percent of the sewerage is treated. A regional planning authority, COMEC,

has existed for nearly 20 years and has generated plans but

no action, because it has no effective powers (Macebo 2004, 547-8).

In conclusion, therefore,

the overwhelming need in all of these great metropolitan areas is for

effective metropolitan governance across the entire Mega-City Region.

Such regions are the new reality of urban existence in the 21st

century. They are, as earlier stated, both the solution and the emerging

problem. They are a Solution because they offer the prospect of

re-equilibrating homes, jobs, and transportation across a new and vast

spatial scale. But they are also the Problem because this

demands effective planning, powers, and action across a very wide

metropolitan scale. Unless this opportunity can be grasped, the evident

risk is that such regions will be characterized by a deepening economic

and social imbalance and polarization, between rich central cities and

marginalized poor peripheries. The signs are already evident. There is

some time to grasp the problem and resolve it – but, perhaps, less than

we think.

Sir Peter Hall

is the Bartlett Professor of Planning and Regeneration at University

College, London, U.K., and the Vice Chairman of Global Urban

Development, also serving as Co-Chair of the GUD Program Committee on

Metropolitan Economic Strategy. His many books include The World

Cities, Cities in Civilization, Urban and Regional

Planning, Cities of Tomorrow, Urban Future 21,

Technopoles of the World, and Silicon Landscapes.

References

Aguilar, A.G., Ward, P.M. (2003) Globalization, Regional

Development, and Mega-City Expansion in Latin America: Analyzing Mexico

City’s Peri-Urban Hinterland. Cities, 20, 3-21.

Booth, C. (1901) Improved Means of Locomotion as a

first Step towards the Cure of the Housing Difficulties of London.

London: Macmillan.

Golub, A. (2004) Brazil’s Buses: Simply Successful.

Access, 24, 2-9.

Hall, P., Pfeiffer, U. (2000) Urban Future 21: A

Global Agenda for Twenty-First Century Cities. London: Spon.

Macebo, J. (2004) City Profile: Curitiba. Cities, 21,

537-550.

McGee, T.G. (1995) Metrofitting the emerging Mega-Urban

Regions of ASEAN. In: McGee, T.G., Robinson, I (ed.) The Mega-Urban

Regions of Southeast Asia. Vancouver: University of British

Columbia Press.

Skinner, R. (2004) City Profile: Bogotá. Cities, 21,

73-81.

UN-Habitat (2001) Cities in a Globalizing World:

Global Report on Human Settlements 2001. London and Sterling, VA:

Earthscan.

UN-Habitat (2003) The Challenge of Slums: Global

Report on Human Settlements 2003. London and Sterling, VA:

Earthscan.

UN-Habitat (2004) The State of the World’s Cities

2004/2005: Globalization and Urban Culture. London and Sterling, VA:

Earthscan.

Wo-Lap, Lam, L. (2002) Race to become China’s Economic

Powerhouse. CNN, 11 June 2002.

Return to top |